What can I do now?

Donald Trump won the 2016 US Presidential election a few hours ago. Since then, the most common thing I've heard from my friends is: "Now what? What can I do now?" They are, like me, disgusted by the bigotry, misogyny, and xenophobia that Trump represents. My answer: organize. And I don't necessarily mean start a new nonprofit. There are plenty of those doing great work already, which is good, because that means you don't have to start from scratch. I'm talking about something bigger. There are millions of people in this country who want it to be safe for women, safe for queer folks, and safe for people with darker skin. There is more love than hate. The hard part has always been channeling it to create change. And we have a new pattern for that, modeled after groups like Occupy and BlackLivesMatter.

Let's say you're organizing a demonstration, or trying to get some legislation passed. Traditionally, you'd notify your mailing list, talk to strangers on the street, and maybe even make cold calls. But these methods are incredibly wasteful. First, they waste time and resources, because most of the people you talk to won't be able/willing to help with your particular issue, and the ones who are willing to help will be lucky to recognize the issue as one they care about while they're wading through all the other emails, petitions, and calls they get. More importantly, these one-time impersonal interactions don't build relationships. Much of the success of Occupy and BlackLivesMatter has been due to their focus on building relationships, both between people and between organizations.

So what's the big deal about relationships? If you think about your friends, you know who might be interested in helping with a particular issue. And if you want to work on an issue, it's a lot easier to get involved if one of your friends already is. You can spend less time dealing with spam email blasts and more time making change. And more generally, our personal relationships have a huge influence on our world-view and our culture. By engaging in activism through meaningful personal connections, we learn to understand different perspectives and bake our principles into our daily lives and habits. And as people participate in different groups, those values and skills become part of a larger activist culture. And that kind of culture-building can be a powerful force to counteract the dangerous political polarization facing the US. And of course, working on things you care about with friends is fun, and fun is an excellent motivator.

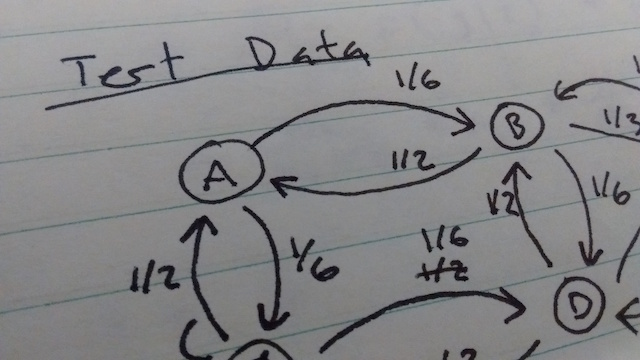

So what does it look like in practice? On top of traditional activism, it looks like meeting regularly with small groups of people who have some common ground (i.e., affinity groups). It's even better if the groups are also diverse in some ways. So for example: people who all live in the same city but work on different issues, or people who work on the same issue but in different formal organizations. On top of the meetings, you can add a mailing list, or an ongoing Google Hangout, or a group message in Signal. When each person is part of multiple groups, skills and ideas quickly spread across the entire activist ecosystem, and it's easy to signal boost a call (or offer) for help to a very large group of people who will actually act on it. If you contact a couple people, and each of them contacts a couple more, and so on, the number of people you reach grows (literally) exponentially. So activism doesn't always have to be about taking steps towards a specific plan, it's sometimes more useful to build a network that allows you to mobilize resources when and where they're needed.

One more time, with feeling! Toward reproducible computational science

My scientific education was committed at the hands of physicists. And though I've moved on from academic physics, I've taken bits of it with me. In MIT's infamous Junior Lab, all students were assigned lab notebooks, which we used to document our progress reproducing significant experiments in modern physics. It was hard. I made a lot of mistakes. But my professors told me that instead of erasing the mistakes, I should strike them out with a single line, leaving them forever legible. Because mistakes are part of science (or any other human endeavor). So when mistakes happen, the important thing is to understand and document them. I still have my notebooks, and I can look back and see exactly what I did in those experiments, mistakes and all. And that's the point. You can go back and recreate exactly what I did, avoid the mistakes I caught, and identify any I might have missed. Ideally, science is supposed to be reproducible. In current practice though, most research is never replicated, and when it is, the results are very often not reproducible. I'm particularly concerned with reproducibility in the emerging field of computational social science, which relies so heavily on software. Because as everyone knows, software kind of sucks. So here are a few of the tricks I've been using as a researcher to try to make my work a little more reproducible.

Databases

When I'm doing anything complicated with large amounts of data, I often like to use a database. Databases are great at searching and sorting through large amounts of data quickly and making the best use of the available hardware, far better than anything I could write myself in most cases. They've also been thoroughly tested. It used to be that relational databases were the only option. Relational databases allow you to link different types of data using a query language (usually SQL) to create complicated queries. A query might translate to something like "show me every movie in which Kevin Bacon does not appear, but an actor who has appeared in another movie with Kevin Bacon does." A lot of the work is done by the database. What's more, most relational databases guarantee a set of properties called ACID. Generally speaking, ACID means that even if you're accessing a database from several threads or processes, it won't (for example) change the data halfway through a query.

In recent years, NoSQL databases (key-value stores, document stores, etc.) have become a popular alternative to relational databases. They're simple and fast, so it's easy to see why they're popular. But their simplicity means your code needs to do more of the work, and that means you have more to test, debug, and document. And the performance is usually achieved by dropping some of the ACID requirements, meaning that in some cases data might change in the middle of a calculation or just plain disappear. That's fine if you're writing a search engine for cat gifs, but not if you're trying to do verifiably correct and reproducible calculations. And the more data you're working with, the more likely one of these problems is to pop up. So when I use a database for scientific work, I currently prefer to stick with relational databases.

Unit tests

Some bugs are harder to find than others. If you have a syntax error, your compiler or interpreter will tell you right away. But if you have a logic error, like a plus where you meant to put a minus, your program will run fine, it'll just give you the wrong output. This is particularly dangerous in research, where by definition you don't know what the output should be. So how do you check for these kinds of errors? One option is to look at the output and see if it makes sense. But this approach opens the door to confirmation bias. You'll only catch the bugs that make the output look less like what you expect. Any bugs that make the output look more like what you expect to see will go unnoticed.

So what's a researcher to do? This is where unit tests come in. Unit tests are common in the world of software engineering, but they haven't caught on in scientific computing yet. The idea is to divide your code into small chunks, and test each part individually. The tests are programs themselves, so they're easy to re-run if you change your code. To do this in a research context, I like to compare the output of each chunk to a hand calculation. I start by creating a data set small enough to analyze by hand, but large enough to capture important features, and writing it down in my lab notebook. Then for each stage of my processing pipeline, I calculate what the input and output will be for that data set by hand and write that down in my lab notebook. Then I write unit tests to verify that my code gives the right output for the test data. It almost always doesn't the first time I run it, but more often than not it's a problem with my hand calculation. You can check out an example here. A nice side effect of doing unit tests is that it gives you confidence in your code, which means you can devote all of your attention to interpreting results, rather than second guessing your code.

Version control

Version control tools like git are becoming more common in scientific computing. On top of making it easy to roll back changes that break your code, they also make it possible to keep track exactly what the code looked like when an analysis was run. That makes it possible to check out an old version of code and re-run an analysis exactly. Now that's how you reproducible! One caveat here: in order to keep an accurate record of the code that was run, you have to make sure all changes have been committed and that the revision id is recorded somewhere.

Logging

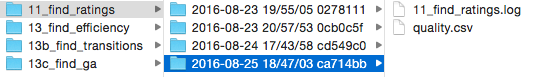

Finally, logging the process of analysis scripts makes it a lot easier to know exactly what your code did, especially years after the fact. In order to help match my results with the version of code that produced them, I wrote a small logging helper script that automatically opens a standard python log in a directory based on the experiment name, timestamp, and current git hash. It also makes it easy to create output files in that directory. Using a script like this makes it easy to know when a script was run, exactly what version of the code it used, and what happened during the script execution.

As for the specific logging messages, there are a few things I always try to include. First, I always have a message for when the script starts and completes successfully. I also wrap all of my scripts in a try/except block and log any unhandled exceptions. I also like to log progress, so that if the script crashes, I can know where to look for the error and where to restart it. Logging progress also makes it easier to estimate how long a script will take to finish.

Using all of these techniques has definitely made my code easier to follow and retrace, but there's still so much more that we can do to make research truly open and reproducible. Has anyone reading this tried anything similar? Or are there things I've left out? I'd love to hear what other people are up to along these lines.

Nonviolent Communication Is Not Emotionally Violent

A friend of mine and I have a running joke that everyone who starts a hackerspace should get a free copy of Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life. Rosenberg was a psychologist who started his career as a mediator, for example, helping resolve conflicts in recently-integrated schools in the U.S. South after the end of racial segregation. Nonviolent Communication, or NVC, was his attempt to codify the strategies he found most successful during his years as a mediator. Since I came across NVC a few years ago, it’s been incredibly helpful in all aspects of my life, including running a hackerspace, which another friend of mine describes as “making sure 200 roommates all get along with each other.” If you look around online, you can read stories from many people who have been helped by NVC, but you can also find some very harsh criticism. Although NVC isn’t the perfect tool for every situation, most of the criticism I’ve seen stems from a misunderstanding of what NVC actually is. So I’d like to clear that up and respond to some common criticisms.

In short, NVC is a framework for identifying the things you need to know about yourself, and the things you need to know about the person you’re talking to, in order to make your conversation a collaboration rather than a competition. It’s often summarized with a four-part template: “(1.) When you [observation], (2.) I feel [emotion], because (3.) I need [need]. (4.) Would you [request]?” This script is a tool to learn which things are most helpful to communicate (observations, emotions, needs, and requests). In practice, NVC doesn’t take the form of reading from a rigid script, but it does communicate the same content. And this is where most criticism gets it wrong. Almost all criticism I’ve seen of NVC describes it as being about how you say something, when it’s really about what you say, and even more importantly, about the self-awareness and empathy you need to exercise in order to put those things into words. So with that out of the way, I’ll address some specific criticisms.

"You have to put the needs of others before your own."

It’s easy to see how someone might think this about NVC. Practicing NVC involves accepting the observations, emotions, and needs of others as valid. If you are thinking of a conversation as a competition, then obviously this means putting someone else ahead of yourself, but not so in NVC. Observations in NVC are meant to be free of judgement, meaning they are statements everyone can agree on. If there are disagreements, you focus on finding the things you do agree on first. There’s no win or lose, just a better mutual understanding of the situation. Next, you have to acknowledge the validity of emotions. But that doesn’t mean giving someone a free pass to act out on those emotions or agreeing with the thinking that led to the emotion. If someone is scared of kittens, I can acknowledge and validate their fear without agreeing that kittens are dangerous and need to be exterminated. Likewise, acknowledging someone’s needs does not mean you need to satisfy that need. And that’s why the last stage is “request” and not “demand.” It comes down to this: you don’t have to put someone else before yourself, but you can’t ask them to put you before themselves either.

But what if listening to someone’s emotions and needs is harmful? Should a victim of violence have to listen to the emotions and needs of the perpetrator? No, not at all. NVC is a tool for communicating, but only if you want to communicate! Also, NVC begins with self-awareness. If you need to avoid talking with a particular person or about a particular subject, NVC encourages you to realize that and act accordingly.

"NVC doesn’t allow you to identify abusive emotions."

This one is true, but it’s not a bug, it’s a feature. Emotions aren’t abusive, actions are. When someone makes this criticism, they’re failing to realize that there’s a difference between how you feel and how you act. Of course not all emotional responses are healthy, but it’s up to each individual to take responsibility for their emotional health. Trying to control someone else’s feelings is emotional violence, which is why it has no place in NVC. But NVC does allow you to respond to someone’s actions. Focusing on actions is beneficial because they’re what actually affect other people and they’re easier to change than emotional responses. Also, abusive behavior often happens because someone experiences a strong emotion, which they see as something that happens to them and therefore not their responsibility, and then believe they’re entitled to act instinctively on that emotion. NVC helps identify harmful behaviors, which can be changed, and helps disentangle them from the emotions that motivated them. For example, if someone cuts you off in traffic you’re likely to experience anger, and that’s a valid emotion, but it doesn’t justify chasing them down and beating them up, even if that’s what you want to do when you’re angry.

"Using NVC is engaging in non-consensual emotional intimacy."

NVC is based on empathy, and this criticism says that empathizing requires consent. The key here is that NVC is meant to be used when emotions are already on the table, meaning someone has already consented. If the clerk at the DMV asks for two pieces of ID, I’m not going to ask them about the deep emotional roots of that need. NVC is more useful when someone is using their emotions to justify a harmful action. But even then, it’s not necessary to discuss their emotions. Yes, part of NVC is identifying your own emotions, but you don’t always need to discuss them, the important part is being conscious of them. In NVC, any (or all) stages (observation, emotion, need, request) can be used internally rather than externally. In a less emotionally intimate context, it’s perfectly acceptable to just make observations and requests. What NVC does is help you remove judgement from observations and figure out what you actually want to ask for.

"NVC can be used to legitimize emotional violence."

The argument here is that harmful statements can be disguised to look like NVC. For example, “When you ruin everything, I feel like you’re an asshole because I need you to do everything I say. Would you stop being horrible?” To anyone familiar with NVC, this is very obviously not NVC. But it is true that people sometimes try to pass emotional violence off as NVC in this way. But the problem isn’t with NVC. Those people would still be committing emotional violence without NVC, they’d just phrase it differently. It is a problem if the victim of emotional violence is tricked into accepting it. And NVC provides precisely the tools necessary to identify emotional violence, even when it’s disguised as NVC or anything else. So yes, bad stuff can be called NVC, but the problem is entirely the bad stuff, not the NVC.

So those are my responses to the most common criticisms I’ve heard. There are some valid limitations of NVC, but the above are not them, and they’re much less severe. One of the main limitations I’ve come across is that, because it relies on cognitive empathy, it doesn’t work very well for anyone on the autistic spectrum or people with certain personality disorders. Another limitation is that when you’re on the receiving end of emotional violence, it can be incredibly tempting to try to teach NVC to whoever is inflicting it, because you can see that there’s a win-win outcome if they could only see it too. But trying to teach someone to dance is not going to make them stop punching you. So word to the wise: if you find yourself trying to teach someone NVC, cut your losses, tell them you need to be left alone and GTFO.

Learning NVC has helped me realize how poorly we understand our own emotions. How often do we say “you made me feel…”? But NVC teaches us that our feelings are the results of our needs and our beliefs, which coincidentally, is the basis of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, one of the most successful evidence-based psychotherapy techniques. And how often do we describe our feelings as “disrespected” or “lied to” or “manipulated”? Which, of course, are not emotions at all, but interpretations of other people’s actions that (while possibly accurate) are only weakly correlated with our emotional responses to those actions. What leads to one person feeling angry, may lead to another feeling sad, or even happy (see, for example, compersion). So based on my experiences, NVC is not the problem. The problem is that we live in an emotionally illiterate and emotionally violent culture. If someone complains that NVC makes it difficult to fight fire with fire, they’re really missing the point.

How not to handle misconduct in an organization

A repeating pattern I've seen from multiple perspectives throughout my life:

1. One member of a community (Alice) repeatedly makes anonymous complains to an administrator (Carol) about another member of the community (Bob).

2. Carol takes action against Bob, giving only vague justification rather than addressing specific behaviors or events.

3. Bob asks for specifics about what the problem is.

4. Carol responds with a long list of vague statements, which at closer inspection contain no additional information.

5. Bob attempts to challenge Carol's action, but 1. the claims are too vague to be falsifiable and 2. any attempts at discussing specific claims are seen as nitpicking.

In practice, this usually occurs in the context of three scenarios, all of which look similar to outside observers:

Scenario A: Bob has done something wrong but has a skewed view of acceptable norms. The process does not clarify those norms and Bob leaves the community thinking "What I did was OK. Those people just don't like me. I'll go do it somewhere else." Observers get them message "What I do doesn't matter, just whether people like me."

Scenario B: Bob has not done anything wrong, but Alice has a skewed (possibly bigoted) view of acceptable norms (e.g., the way "wearing a hoodie" becomes "acting like a thug" for black men). Carol has unknowingly empowered Alice's bigotry.

Scenario C: Both Alice and Bob have a misunderstanding that could be resolved, but never is. An opportunity to strengthen the relationship between two members of the community and to clarify norms is lost.

None of these seem particularly desirable from a social justice or community standpoint. It's pretty easy to get a different outcome though, by 1. having a clear code of conduct for communities, and 2. separating behaviors from character judgements (as in NVC). But I haven't yet come across many communities that do this well.

Hackers are Whistleblowers Too (live blog from HOPE XI)

Naomi Colvin, Courage Foundation

Nathan Fuller, Courage Foundation

Carey Shenkman, Center for Constitutional Rights

Grace North, Jeremy Hammond Support Network

Yan Zhu, friend of Chelsea Manning

Lauri Love, computer scientist and activist

Naomi begins. Courage foundation started in July 2014 to take on legal defense for Edward Snowden. They believe there is no difference between hackers and whistleblowers when they’re bringing important information to light. Information exposure is one of the most important triggers for social action. The foundation has announced their support for Chelsea Manning, who is beginning her appeal.

Carey wants to talk about public interest defenses. In the US, politicians call for whistleblowers to return to the US and present their motivations and “face the music” as part of their civil disobedience. In reality, the Espionage Act and the CFAA do not allow whistleblowers to use public interest motivations as a defense or use evidence to demonstrate a public interest. Whistleblowers like Ellsberg have called for public interest exceptions to the Espionage Act and CFAA. It’s important to protect civil

Grace: Jeremy Hammond hacked Stratfor with AntiSec/Anonymous and leaked the files on WikiLeaks. Tech has an incredible power to bring movements together. This requires some tech people to move outside of their comfort zone to interact with activism around other (non-technical) issues.

Yan: Chelsea really loves to get letters and reads every one she receives. While at MIT, Yan met Chelsea through the free software community. Chelsea’s arrest was the first time Yan saw the reality of whistleblowing and surveillance. Chelsea is very isolated and only gets 20 people on her phone list. To add someone, she has to remove someone else. Visitors have to prove they met her before her arrest in order to visit. She reads a statement from Chelsea Manning.

Lauri Love was arrested in 2013 in the UK without charges and later learned that he was charged in the US, which is very unusual, not having been alleged to have committed any crimes within the US. The problems with the CFAA are being used to contest his extradition to the US. Lauri greatly appreciates the support of the Courage Foundation

Lauri asks Carey: The UK allows you to present a defense of necessity, although it’s difficult. Can that happen in the US?

Carey: It’s difficult to say. The CFAA has always been controversial. The CFAA was passed in 1986, literally in response to the movie Wargames, which sparked the fear of a “cyber Pearl Harbor.”

Grace: Jeremy Hammond’s hacks were politically focused, but there were absolutely no provisions for acts of conscience in his defense. In fact, having strong political views leads to harsher treatment.

Lauri: Can we bypass the court system and national council of conscience?

Lyn: Mother of Ross Ulbricht, creator of silk road. Judges cited political views as reasons for the severity of Ross’s sentence. The court system also allows prosecutors to break the letter of the law when it is done in “good faith” while it doesn’t allow defendants to do so.

Lauri: It’s important to be vocal about these details. It

Audience question: CFAA prosecutions are really about politics, not about computers. It seems like some issues like gay marriage can change very quickly in American culture. What can be done to create these changes?

Grace: We couch issues in certain terms. What people find acceptable or unacceptable is often determined by perspective and simplified views of “legal” vs. “illegal.”

SecureDrop: Two Years On and Beyond

Live notes from HOPE XI

Garrett Robinson, CTO of Freedom of Press Foundation and Lead Developer of Secure Drop

Secure Drop debuted at HOPE X in 2014. FPF was founded in 2012, initially to crowd fund for WikiLeaks. They’ve been doing more crowdfunding for various open-source encryption tools for journalists, and for whistleblower Chelsea Manning’s legal defense. They’re also suing the federal government to respond to FOIA requests. But their main project is SecureDrop.

Over the past couple years, a lot of the plans for SecureDrop happened, and a lot changed. Last year, SecureDrop was installed at 12 independent organizations. They are a mixture of big and small media outlets, and activist nonprofits. All but one still uses the software, and several more have installed it, with a current total of 26 active installations. They’ve improved documentation to make installation easier. There’s a high demand. More organizations are waiting for help in installation and training.

FTF intentionally discourages media outlets from acknowledging which information was received via SecureDrop, which makes outreach complicated. SecureDrop was acknowledged as being used by hackers who exposed violations of attorney-client privilege by prison phone provider Securus.

As an internet service open to the public, SecureDrop attracts trolls. At The New Yorker, over half of their submissions were fiction or poetry.

Garrett gives an overview of how SecureDrop works. There are three main components: a network firewall, a monitor server, and an application server. When a source wants to submit to SecureDrop, they use Tor without JavaScript. They are assigned a secure pseudonym. They are then able to have a back-and-forth conversation with journalists. The journalist logs into the document interface Tor hidden service They are presented with a list of documents. All files are stored encrypted, transferred using USB or CDs to an air-gapped computer for decryption, reading, and editing.

The current project goals are: 1. keep SecureDrop safe, 2. Make SecureDrop easier for journalists to use, and 3. make SecureDrop easier to deploy and maintain.

Keeping SecureDrop safe. Tor hidden services enable end-to-end encryption with perfect forward secrecy without using certificate authorities. The NSA has had difficulty e-anonymizing Tor (as of 2012). Since then, the FBI has been able to install malware on users’ computers allowing the de-anonymization of Tor hidden services. In 2014, Tor identified a possible attack, which turned out to be a large-scale operation coordinated by multiple states, called Operation Onymous. This attack was made possible by researchers at CMU working with the FBI. Tor was able to blacklist the attackers and block them out eventually. Directories of hidden services have been shown to enable correlation attacks. A 2015 USENIX paper by Kwon et al. has shown that it’s possible to use machine learning and a single malicious Tor node to de-anonymize SecureDrop users, without leaving a trace.

Making SecureDrop easier to use. Doing experiments with using software isolation like Qubes to make air-gaps unnecessary. If the system isn’t usable, journalists either don’t use it or work around the security in harmful ways.

Making SecureDrop easier to deploy. There is a support process in place, but it’s inefficient. The documentation, when printed out, is 138 places. As an aside, Garrett wants a Guy Fawkes toaster.

Garrett wants to live in a world where SecureDrop is obsolete. He wants to live in a world where standard technology enables privacy at the level of SecureDrop. There’s been some progress. Open Whisper Systems has developed Signal and enabled end-to-end encryption for WhatsApp (even though there are security concerns with metadata collection).

The Onion Report (HOPE XI live blog)

Notes taken at HOPE XI.

Presenters:

asn

Nima Fatemi

David Goblet

Nima gives some basic stats. New board, 6 members. 8 employees, 12 contractors. 40 volunteers. 7000 relay operators. 3000 bridge operators. Dip in relay operators around April 2016 with corresponding spike in bridge operators.

Five teams work on TOR. The Network team is working on better crytography (Ed25519 and SHA3). TOR depends on 8 trusted computers around the world that maintain consensus, which are sometimes attacked with DDoS. There is now a backup list that can be used when no consensus is reached.

Application team doing ongoing development on the TOR browser. Porting the browser to mobile platforms. Doing research and development on sandboxing and usability. Also working on TorBirdy (email) and Tor Messenger (XMPP, OTR).

The UX team collaborating with security usability researchers. Can’t collect usage data because of privacy. Running user studies. Now have a security “slider.” Now display routing chain.

Community team drafting social contracts, membership guidelines, etc. Doing outreach, including the Library Freedom Project.

Measurement team received $152,500 grant from Mozilla. Revamping entire metrics interface.

Ahmia is a search engine for onion services. TOR now gives badges to relays.

How Anonymous narrowly evaded being vilified as terrorists (HOPE XI live blog)

Notes taken at HOPE XI.

Gabriella Coleman, Anthropologist, Professor, McGill University

Biella spent several years studying Anonymous. Found them “confusing, enchanting, controversial, irreverent, interesting, unpredictable, frustrating, stupid, and really stupid.” She expected to have to convince people they weren’t terrorists, but that didn’t happen.

The media usually refers to Anonymous as activists, hacktivists, or vigilantes, rather than terrorists. Pop culture has taken up Anonymous, which has helped inoculate them from the terrorism level.

The label can be used in the media to political ends, example: Nelson Mandela being labeled a terrorist. In France, the Tarnac 9 were arrested as terrorists for stopping trains, but the change was changed. In Spain, puppeteers were arrested for “inciting terrorism” and placed in jail for five days, but the case was thrown out. Common privacy tools like TOR and riseup can lead to suspicions of terrorism. Police and others in the US have tried to get Black Lives Matter designated as a terrorist organization.

Biella cites “Green is the New Red.” Since September 11, terrorism has been redefined to suit political whims, often impacting radical activists such as animal rights activists. What was once “monkey wrenching” or “sabotage” is now considered “terrorism.” A group called the SHAC7 were convicted under the Animal Enterprise Act for running a website that advocated for animal liberation. Many received multi-year jail sentences.

Focusing on technology, the language of terrorism has often been used to describe hacking. Biella was concerned she’d be targeted by the FBI for studying Anonymous. Targets of Anonymous described them as terrorists in the media. The hacktivist Jeremy Hammond was found to be on the FBI terrorism watch list, but because he was an environmental activist, not because he was a hacktivist. GCHQ described Anonymous and LulzSec as bad actors comparable to pedophiles and state-sponsored hackers. In the US, Anonymous was used as a primary example during Congressional hearings on cyberterrorism. The Wall Street Journal published a claim by the NSA that Anonymous could develop the ability to disable part of the US electricity grid.

Timing influenced how the public received these claims. The government compared Wiki-Leaks to Al-Quaeda, and compelled Visa and PayPal to freeze their accounts. These actions were seen as extreme by the public, and Anonymous launched Operation Payback, a DDoS of the PayPal blog, to protest. The media framed the event as a political act of civil disobedience. A month later, Anonymous contributed to social revolutions in the Middle-East and Span, and in Occupy. Anonymous has been described as incoherent for being involved in many different things, but this flexibility has helped inoculate them against the terrorist label. Anonymous is a “Multiple Use Name,” as described by Marco Deseriis.

The Guy Fawkes mask has played an important role. While the use of the mask was largely an accident, but carries connotations of resistance. These connotations were historically negative, but became positive with Alan Moore’s “V for Vendetta” and its film adaptation. There’s a feedback cycle between reality and fiction about resistance to totalitarian states. There’s an astounding amount of media about hackers. Biella’s favorite is called “Who Am I.” There’s even a ballet based on the story of Anonymous. RuPaul discussed with John Waters as a type of youthful rebellion. In contrast, animal rights activists are often portrayed as dangerous and unlikable.

ISIS uses social tactics similar to Anonymous. The difference between the two groups has created a contrast, amplified by Anonymous declaring war on ISIS.

In 2012, the Anti-Counterfeit Trade Agreement was under debate. The Polish population protested ACTA. Anonymous got involved with Operation ANTI-ACTA in support of Polish citizens. A number of Polish members of parliament wore Guy Fawkes masks to show disapproval for ACTA. The gesture helped to legitimate Anonymous and its tactics.

Tides can change very quickly. An infrastructure attack tied to hacktivists could turn the public against Anonymous. Art and culture really matter. Sometimes the world of law and policy sees art and culture as “soft power,” but Biella argues this is a false dichotomy. She appeals to people who work in the arts to continue, perhaps writing children’s books about hackers.

Phineas Fisher created a brilliant media hack on Vice News. Vice arranged an interview with Fisher, who requested to be represented by a puppet.

What the hack?! Perceptions of Hackers and Cybercriminals in Popular Culture (HOPE XI live blog)

These notes taken at HOPE XI

What the hack?!

Aunshul Rege, Assistant Prof in Criminal Justice at Temple University

Quinn Heath, Criminal Justice student at Temple University

Aunshul begins. Work based on David Wall’s seven myths about the hacker community. How does the media portrayal of hacking differ from reality? Three objectives: 1. get hacker community’s perspective, 2. how does the hacker community feel about Wall’s myths, 3. general thoughts on how the media interacts with the hacker community. Work conducted by interviews of self-identified hackers at HOPE X.

Quinn starts on the first objective. What makes someone a hacker? Plays some interviews from HOPE X. Every hacker had a unique story, but there were common threads. Many hackers felt they had been hackers from a young age. There was also a common thread of hacking bringing empowerment.

First myth: cyberspace is inherently unsafe. Mixed response from interviewees. Some felt that the internet was “just a pipe,” while others believed that as a human system, it empowered misuse.

Second myth: the super hacker. Interviewees believed that no one person knows everything. Highly unrealistic. Real people just aren’t as interesting.

Third myth: cybercrime is dramatic, despotic, and futuristic.

Fourth myth: hackers are becoming part of organized crime. Many felt there was some truth to this.

Fifth myth: criminals are anonymous and cannot be tracked. Everybody uses handles, but you have to go through a single IP. Everyone leaves a trace. The only way not to get caught is to not do anything worth getting caught over.

Sixth myth: cybercriminals go unpunished and get away with crime: Law enforcement is making examples out of people in the hacker community. You have to be careful about what you type into a terminal, assume it will be used against you in the worst possible light. Media portrayal translates into harsher prosecution for hackers than for violent criminals. The CFAA is abused by law enforcement, for example in the Aaron Swartz case.

Seventh myth: users are weak and not able to protect themselves. Media focuses too much on companies and not enough on the users whose data is released. People are becoming less scared of technology.

Quinn moves on to common themes. One was a common objection to the way the word “hacker” is used in the media. The word is ambiguous, but has been used by the media in a much narrower and disagreeable way.

Women are underrepresented in the hacker community, even though the community tends to be more liberal. Women in technology sometimes aren’t presented as hackers because they don’t fit existing media stereotypes.

Hackers are portrayed as geeky, nerdy, boring, caucasian males. But there are hackers of all races. Sometimes hackers of color are presented as a vague formless threat.

Hackers are presented in a polarized way: either losers or dangerous and powerful. Women in the media are always attractive and sexualized and/or goth.

The media sometimes focuses on the hack, and sometimes on the hacker. It’s easier to get information on a hack, and easier to twist the facts to suit the story the media or company want to convey. The media likes to have a face and a personality, but that’s rare.

How does the news interact with the hacker community? There needs to be better journalism. The media takes snippets that don’t give the full story, but shape public opinion.

What about movies? Most of what happens is inaccurate. “They’re not going to make a movie about people staring at computer screens,” it would be “boring as hell.” The movies and media don’t pay tribute to the social engineering aspect. It makes sense that Hollywood would do this, but less so that the news does.

What about the 1995 movie “Hackers”? It’s almost a parody. It’s old and outdated, even for when the movie was set. It’s fun, but not good or accurate. It stereotypes what hackers are. Almost everyone mentioned this movie, and loved it in a “it’s so bad it’s good” kind of way.

Over time, the hacker stereotype has gone from the teenage prankster in the 80s, to dangerous cyber-warriors or weird, young, and soon-to-be-rich.

Hackers are careful about using the word because they’re sensitive to how people will perceive it. They described a strong personal impact due to the media portrayal. But the community remains strong.

What kind of movie would hackers make about hackers? It would be fun to flip all the stereotypes. Most hacking is boring from the outside, so it would need to be dramatized, but it could be more realistic.

Anshul: interested in more information on race, gender and age. Also wants to know how the hacking community is influenced by media stereotypes. Will be publishing this work soon.

That emoji. I do not think it means what you think it means.

When my database threw an unexpected error, I looked up the cryptic code in the message, and fell down a bizarre click-hole about a surprisingly controversial cultural symbol: the "woman with bunny ears" emoji. That's the official title at least, but it has variously been interpreted as "ballerinas" or "Playboy bunnies" or "Kemonomimi" (a human character with animal features, common in Japanese media). Different visual representations have leaned towards evoking different interpretations. These interpretations are left up to implementors and not part of the Unicode standard. There can even be differences between implementation versions from the same vendors. For instance, in iOS 8.3, Apple increased the size of the bunny ears, which had previously looked more like barrettes. For many people, this shifted the meaning of the symbol from "dancers/dancing" to "porn stars," and undoubtedly led to some rather awkward miscommunications. It goes to show that we're still figuring out how to use emoji. And perhaps it's worth looking up your favorite emoji to make sure you're not sending mixed signals to your friends.