Social Capitalism

CW: refers to sexual assault

When high-profile individuals are outed for patterns of sexual assault, their friends and collaborators always seem to be completely surprised, unlike the other people who inevitably come forward as having been assaulted. Right now, the national dialogue is about Harvey Weinstein, but the same story seems to be repeating itself every few months. Closer to home, several high profile information security activists and researchers have recently been called out for sexual assault. Activists? Committing sexual assault?! The people who are supposed to spend their time and energy making the world better?!?! Yes, them. In fact, it happens so often, there's a book about it. So how is it that high-profile profile people can hide their abusive behavior from their friends, and convince the wider world that they're virtuous moral authorities? And how can it happen so very often? What if it’s not a coincidence? What if people make it to positions of power and visibility specifically because they are willing to take advantage of others? A certain type of high-visibility success is built on social capital, and the perverse incentives of financial capitalism apply just as well to social capitalism.

First, let me be clear about what I mean by “capitalism.” Capitalism is many things, but at its core, it’s a system where people who have resources (land, equipment, money) lend it to those who need it, and then take a cut of what they make. Capitalism is arranged so that the only way to be successful is make someone wealthy even wealthier. The same is true for social capital. Social capital is, as the saying goes, “who you know.” Social capital is introductions to influential people. It’s access to insider information. It’s going out for drinks with the people who make decisions. And just like in financial capitalism, the way to be successful is to help those who are already are, even if it’s at the expense of those who aren’t. This capitalist social dynamic holds even in the most progressive or anti-capitalist communities.

If you look at an industry like entertainment, you have powerful and influential people like Harvey Weinstein at the top, and a lot of folks competing for their favor. Let’s say you’re one of the folks in the middle, and you see someone powerful abusing that power. What do you do? Well, you could take a stand and call them out. In the best case scenario, they’re held accountable, but then you’ve lost any social capital you’ve built up with them. But even worse, so have your peers who were banking on that social capital, and a lot of them will blame you. And other powerful people are more likely to see you as a liability. Of course the powerless folks who were being taken advantage of will be appreciative, but they have nothing to offer you. Under social capitalism, those who speak up for the powerless fade into irrelevance, while those who turn a blind eye climb to the top. So is it really that surprising that the top is rotten with selfish amorality?

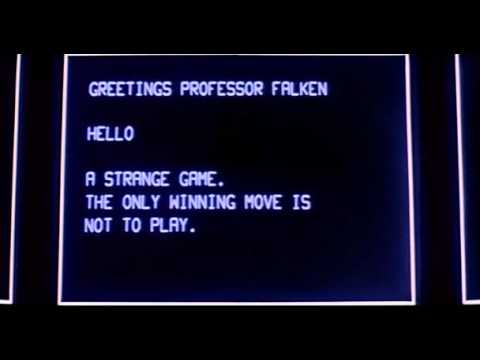

So what's to be done? It's tempting to "play the game" to try to change things once you're on top. Maybe it’s possible, but from where I stand, it looks like a long, hard journey that changes most people, and not for the better. So there's the catch 22. You can't change anything without power, and you can't get power without enabling the very behavior you're trying to change. As a sentient AI in a 80s hacker movie once said, "the only winning move is not to play." In my experience, there are people out there making a big difference by building alternative social systems rather than supporting corrupt ones, they just don't get a lot of press. It can be hard to tell the difference between someone who genuinely wants to do good, and someone who wants to be known as a person who does good. But if you want to spot a social capitalist, just look at how they treat people who don't have anything they want.

What can I do now?

Donald Trump won the 2016 US Presidential election a few hours ago. Since then, the most common thing I've heard from my friends is: "Now what? What can I do now?" They are, like me, disgusted by the bigotry, misogyny, and xenophobia that Trump represents. My answer: organize. And I don't necessarily mean start a new nonprofit. There are plenty of those doing great work already, which is good, because that means you don't have to start from scratch. I'm talking about something bigger. There are millions of people in this country who want it to be safe for women, safe for queer folks, and safe for people with darker skin. There is more love than hate. The hard part has always been channeling it to create change. And we have a new pattern for that, modeled after groups like Occupy and BlackLivesMatter.

Let's say you're organizing a demonstration, or trying to get some legislation passed. Traditionally, you'd notify your mailing list, talk to strangers on the street, and maybe even make cold calls. But these methods are incredibly wasteful. First, they waste time and resources, because most of the people you talk to won't be able/willing to help with your particular issue, and the ones who are willing to help will be lucky to recognize the issue as one they care about while they're wading through all the other emails, petitions, and calls they get. More importantly, these one-time impersonal interactions don't build relationships. Much of the success of Occupy and BlackLivesMatter has been due to their focus on building relationships, both between people and between organizations.

So what's the big deal about relationships? If you think about your friends, you know who might be interested in helping with a particular issue. And if you want to work on an issue, it's a lot easier to get involved if one of your friends already is. You can spend less time dealing with spam email blasts and more time making change. And more generally, our personal relationships have a huge influence on our world-view and our culture. By engaging in activism through meaningful personal connections, we learn to understand different perspectives and bake our principles into our daily lives and habits. And as people participate in different groups, those values and skills become part of a larger activist culture. And that kind of culture-building can be a powerful force to counteract the dangerous political polarization facing the US. And of course, working on things you care about with friends is fun, and fun is an excellent motivator.

So what does it look like in practice? On top of traditional activism, it looks like meeting regularly with small groups of people who have some common ground (i.e., affinity groups). It's even better if the groups are also diverse in some ways. So for example: people who all live in the same city but work on different issues, or people who work on the same issue but in different formal organizations. On top of the meetings, you can add a mailing list, or an ongoing Google Hangout, or a group message in Signal. When each person is part of multiple groups, skills and ideas quickly spread across the entire activist ecosystem, and it's easy to signal boost a call (or offer) for help to a very large group of people who will actually act on it. If you contact a couple people, and each of them contacts a couple more, and so on, the number of people you reach grows (literally) exponentially. So activism doesn't always have to be about taking steps towards a specific plan, it's sometimes more useful to build a network that allows you to mobilize resources when and where they're needed.

Hackers are Whistleblowers Too (live blog from HOPE XI)

Naomi Colvin, Courage Foundation

Nathan Fuller, Courage Foundation

Carey Shenkman, Center for Constitutional Rights

Grace North, Jeremy Hammond Support Network

Yan Zhu, friend of Chelsea Manning

Lauri Love, computer scientist and activist

Naomi begins. Courage foundation started in July 2014 to take on legal defense for Edward Snowden. They believe there is no difference between hackers and whistleblowers when they’re bringing important information to light. Information exposure is one of the most important triggers for social action. The foundation has announced their support for Chelsea Manning, who is beginning her appeal.

Carey wants to talk about public interest defenses. In the US, politicians call for whistleblowers to return to the US and present their motivations and “face the music” as part of their civil disobedience. In reality, the Espionage Act and the CFAA do not allow whistleblowers to use public interest motivations as a defense or use evidence to demonstrate a public interest. Whistleblowers like Ellsberg have called for public interest exceptions to the Espionage Act and CFAA. It’s important to protect civil

Grace: Jeremy Hammond hacked Stratfor with AntiSec/Anonymous and leaked the files on WikiLeaks. Tech has an incredible power to bring movements together. This requires some tech people to move outside of their comfort zone to interact with activism around other (non-technical) issues.

Yan: Chelsea really loves to get letters and reads every one she receives. While at MIT, Yan met Chelsea through the free software community. Chelsea’s arrest was the first time Yan saw the reality of whistleblowing and surveillance. Chelsea is very isolated and only gets 20 people on her phone list. To add someone, she has to remove someone else. Visitors have to prove they met her before her arrest in order to visit. She reads a statement from Chelsea Manning.

Lauri Love was arrested in 2013 in the UK without charges and later learned that he was charged in the US, which is very unusual, not having been alleged to have committed any crimes within the US. The problems with the CFAA are being used to contest his extradition to the US. Lauri greatly appreciates the support of the Courage Foundation

Lauri asks Carey: The UK allows you to present a defense of necessity, although it’s difficult. Can that happen in the US?

Carey: It’s difficult to say. The CFAA has always been controversial. The CFAA was passed in 1986, literally in response to the movie Wargames, which sparked the fear of a “cyber Pearl Harbor.”

Grace: Jeremy Hammond’s hacks were politically focused, but there were absolutely no provisions for acts of conscience in his defense. In fact, having strong political views leads to harsher treatment.

Lauri: Can we bypass the court system and national council of conscience?

Lyn: Mother of Ross Ulbricht, creator of silk road. Judges cited political views as reasons for the severity of Ross’s sentence. The court system also allows prosecutors to break the letter of the law when it is done in “good faith” while it doesn’t allow defendants to do so.

Lauri: It’s important to be vocal about these details. It

Audience question: CFAA prosecutions are really about politics, not about computers. It seems like some issues like gay marriage can change very quickly in American culture. What can be done to create these changes?

Grace: We couch issues in certain terms. What people find acceptable or unacceptable is often determined by perspective and simplified views of “legal” vs. “illegal.”